Before I came to Ladakh, I was amazed that the only way to enter or leave in the winter is by flight. Then I went to Padum, the last "big" town on the dead-end road to the Zanskar region of Ladakh, and discovered that the only road is closed by winter snows for half the year - and there are no flights. Then I walked the two days to Phuktal Monastery, and couldn't really imagine winter there. The main route in and out during the height of winter is walking along the frozen river, which is termed traveling along the chaddar. Chad means "to freeze" and dar means "your ass off." The river doesn't always freeze through evenly, so falling through the ice is a definite risk. And in late winter, when the ice is starting to melt, the high passes are still blocked by snow, so even the relative comfort of walking along an ice-covered river is no longer available. I can't imagine. (And I complain about slow traffic at home. Hah!)

But not surprisingly, these are a hardy people. At Sonam's wedding, her younger brother, Tenzin, said he was walking to Manali in four days; its regularly trekked by tourists in ten days. When I said that sounded hard, he said, "NOT hard! You just walk five hours in the morning, have lunch, then walk five hours in the afternoon. Not hard." There was no bravado in his statement - he just didn't think it was hard.

I witnessed one of the results of the isolation of the area. In a well-touristed, relatively affluent village not far from the monastery, I saw a woman sitting on the ground with her head in her hands, like she was in pain. I asked the shopkeeper, standing beside her, if she was okay. She pointed to a rock, and on the rock I saw a long, bloody molar, freshly pulled, without any painkiller - not even aspirin. (The tooth had a cavity in it about the size of a small pea.) The patient/victim was stoic and silent, even though she was obviously in a lot of pain. The shopkeeper/dentist prepared a natural remedy of cooked barley flour, butter and sugar that the patient spooned into the hole in her jaw.

That seemed adequately intense, but then the shopkeeper/dentist took the dental pliers from her kid, who was playing with them on the ground, wiped them off, and went in to extract a second tooth! (Would we EVER go to the dentist if this is what it was like?) Two attempts and two bits of broken tooth later (the root stayed in) and the shopkeeper/dentist proclaimed "Done." As crude as the sidewalk dentist in Varanasi was, at least he used Novocaine. I asked why she didn't use some painkiller, and she said, "Because sometimes it doesn't work." That's your answer?! That's the sort of bewildering logic that is so common here that I didn't even ask any follow-up questions. It turns out that the shopkeeper did have some sort of government-sponsored nurse training, although I'm not sure it was on display on this day.

In spite of the ancient culture and simple existence of the people in the area, most of the villagers are relatively well off. They have large houses, plenty to eat, and many can afford to send their children to boarding schools, either in Leh (the capital of Ladakh,) or Manali or Jammu. The kids are typically at school for 10 months a year, and only home for two. All the subjects are taught in English (which is true of many schools in India) so the kids are quite fluent in English, and know a fair bit about the world. I wonder, though, how many of these well-educated kids will choose to stay in such a simple and remote village life.

I thought I was writing a letter about monks. But if my Newsletter McNuggets get too long, they won't get read. So the monk stories will have to wait...

Love,

Dave

p.s. I've left Zanskar, and I'm now in Leh. I'm plotting my (gulp) return to San Francisco for work in about two weeks.

There are six photos below:

I met this man walking on the trail. He was really a gentle soul.

You can just make out the trail on the left side of the photo.

A view from the house where I spent one night on the walk.

A kitchen inside a small tea shop.

Carrying water in a village where I don't believe anyone had running water.

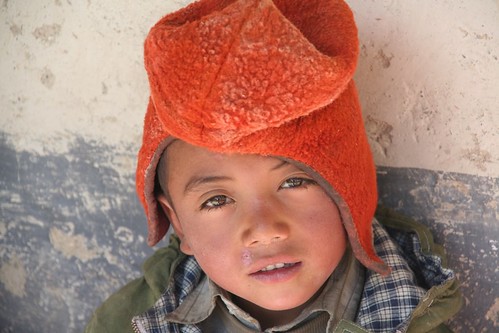

It doesn't take much - hold out your camera, smile, and watch it unfold.

(The End)